WARNING: SPOILERS FOR SEASON 1

I’m pretty sure I screamed in delight when I opened Netflix to see Aggretsuko. For the uninitiated, this series features shorts about Retsuko – an adorable red panda with a calm, docile appearance that belies roiling rage begging to be released. Unlike the shorts, however, the Netflix series takes time to weave a cohesive narrative and delve a bit deeper into the motivations and struggles of our favorite red panda and her similarly adorable animal friends (including Fenneko, a fennec with a hilarious penchant for cyber-stalking, and Haida, a good-natured, if somewhat awkward spotted Hyena).

I watched the Aggretsuko shorts before it became a Netflix series when I was still in college, so this kind of reality was still a far-off mirage. Now that I’m in the same stage (and age) in life as Retsuko, the scenarios hit a little harder, and are a little less easy to chuckle at. Retsuko steels herself daily against the onslaught of struggles (unfortunately) typical of an average workplace – power harassment and sexism (courtesy of the porcine Boss Ton and his lackey/Professional BootLicker™ Komiya), drama and gossiping (courtesy of the brown-nosing deer, Tsunoda, and the garrulous, gossipy hippo, Kabae), and perhaps worst of all, Retsuko’s own helplessness and self-doubt.

Normally, Retsuko’s way of dealing with the mundane, soul-killing routine her life has become since joining the trade firm at 20 is to patronize a nearby karaoke establishment and scream out her emotions to death metal for catharsis. It’s only until her free-wheeling, peripatetic friend Pukko (a pink cat) makes an appearance and asks Retsuko if she’s actually happy despite her stable life that Retsuko begins to re-evaluate.

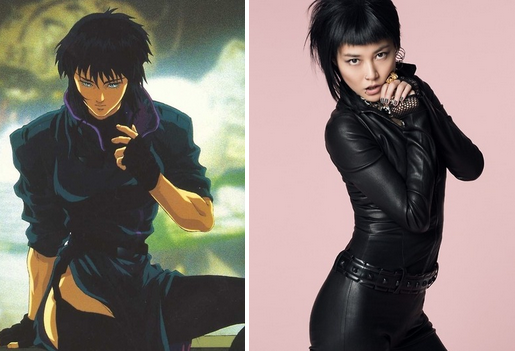

She then makes a series of well-intentioned, yet clumsy and misguided moves that thankfully land her in the hands of some kind older women who outrank her at the same company, Washimi (a prim, precise secretary bird) and Gori (an effusive, enthusiastic gorilla).

While Retsuko’s plight was relatable up to a point, sometimes I found her decisions to be beyond a little misguided, crossing over into just plain naive.

When she gets excited over the prospect of being able to leave her current job to work for Pukko’s business venture, she doesn’t think to ask Pukko detailed questions about the business. This backfires hard when she starts giving her supervisors sass at work (ALWAYS a bad idea. Also, searching for quitting-work stuff on the work server? Retsuko? More like Reckless-ko), leading to her demotion. But I guess that’s to be expected when you’ve lived your whole life more or less how you’re ’supposed’ to.

In modern society, the script we’re “meant” to follow usually looks a little something like: go to school, get a degree, find a spouse, raise kids, work for life, retire. Some people expect to follow this script, and there’s nothing wrong with that, necessarily, if that is what you want for your life. But there’s a difference between wanting something because you want it and wanting something because you’re “supposed” to want it.

The thing is, in my experience, if you run after something just to escape something else, eventually you’ll find yourself wanting to escape that, as well. Because you’re choosing out of desperation, not passion. And if you walk (or run) around the problem, you’ll find yourself right back at square one.

Retsuko decides at one point that she can always get married and escape the demands of work life and the responsibility of supporting herself. Thankfully, Washimi and Gori are quick to point out that she’d be trading one set of problems for another – the drudgery of grunt work for the drudgery of housework. (Always choose the option where you have the reins of your own finances.)

But the really big elephant in the room (no, not the company president Washimi works under) is the, uhm. Dysfunctional questionable way of dealing with her emotions – the whole death metal schtick that drew many viewers to Aggretsuko. Retsuko’s situation is a recipe for frustration, to be sure, though I wonder if she’d be screaming well into her 30s if not for the intervention of Gori and Washimi, and hell, even Pukko to some extent.

In the end, due in part to a whirlwind ‘romance’ she has mostly by herself with another red panda who works at the company, Retsuko becomes able to admit to herself when she wants something outside of the script laid before her. There’s signs of a possible connection between she and Haida, someone who’s shown he cares for her in his own fumbling, indirect way. Like their possible budding romance, navigating the waters of early 20s life is something I’ve found that’s best taken one day a time, being sure to move toward something desired instead of away from something undesirable.

Here’s hoping for a season 2!